It’s really easy to get started with Flask on PythonAnywhere, but if it’s the first database-backed website you’ve ever built, it can feel a little daunting. Here are some step-by-step instructions. We’ll build a really simple website – just a page where anyone can leave a comment, with the comments stored in a database so that they last forever. We’ll also password-protect it so that it doesn’t fill up with spam. Here’s what it will look like:

We assume that you’ve got a little bit of basic Python and HTML knowledge – for example, that you’ve done an online course in both of them. Everything else we’ll explain as we go along. Let’s get started!

First steps¶

Firstly, create a PythonAnywhere account if you haven’t already. A free “Beginner” account is enough for this tutorial.

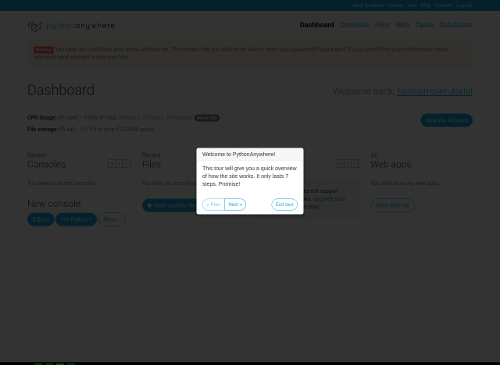

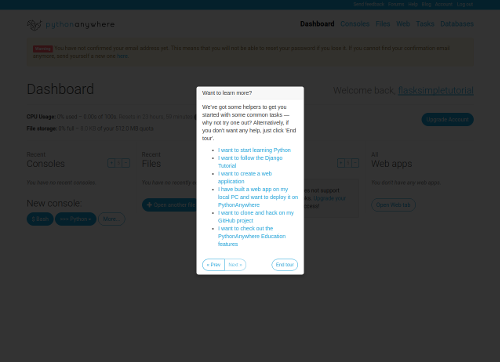

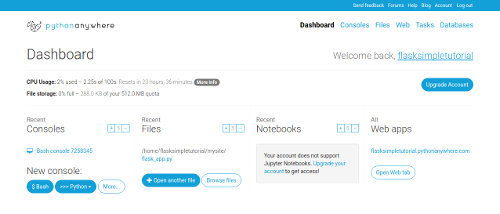

Once you’ve signed up, you’ll be taken to the dashboard, with a tour window. It’s worth going through the tour so that you can learn how the site works – it’ll only take a minute or so.

At the end of the tour you’ll be presented with some options to “learn more”. You can just click “End tour” here, because this tutorial will tell you all you need to know.

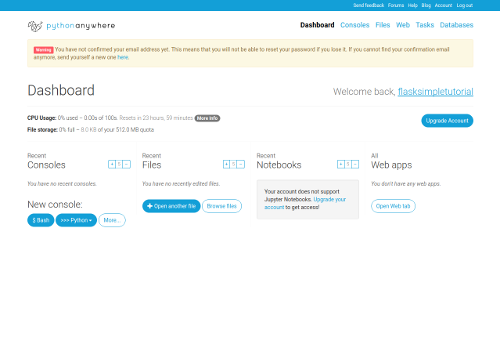

Now you’re presented with the PythonAnywhere dashboard. I recommend you check your email and confirm your email address – otherwise if you forget your password later, you won’t be able to reset it.

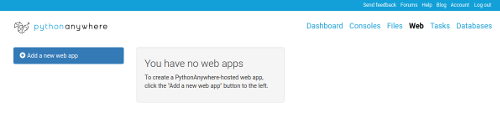

Now, click on the “Web” link near the top right, and you’ll be taken to a page where you can create a website:

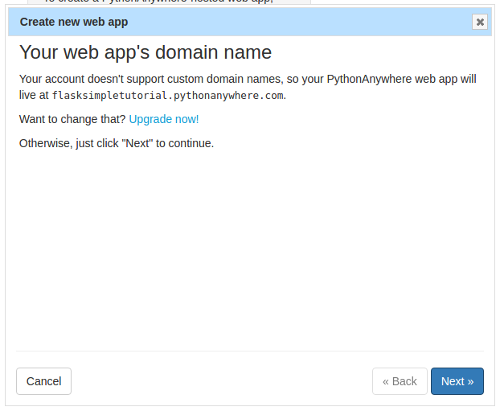

Click on the “Add a new web app” button to the left. This will pop up a “Wizard” which allows you to configure your site. If you have a free account, it will look like this:

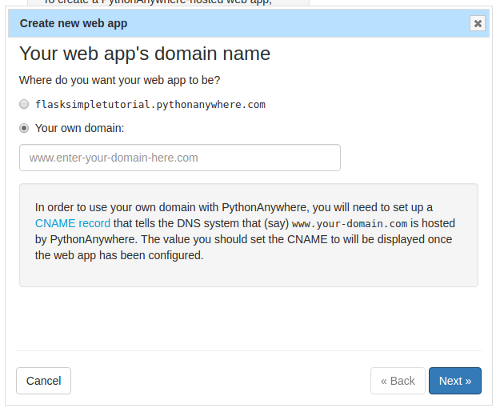

If you decided to go for a paid account (thanks :-), then it will be a bit different:

What we’re doing on this page is specifying the host name in the URL that people will enter to see your website. Free accounts can have one website, and it must be at yourusername.pythonanywhere.com. Paid accounts have the option of using their own custom host names in their URLs.

For now, we’ll stick to the free option. If you have a free account, just click the “Next” button, and if you have a paid one, click the checkbox next to the yourusername.pythonanywhere.com, then click “Next”. This will take you on to the next page in the wizard.

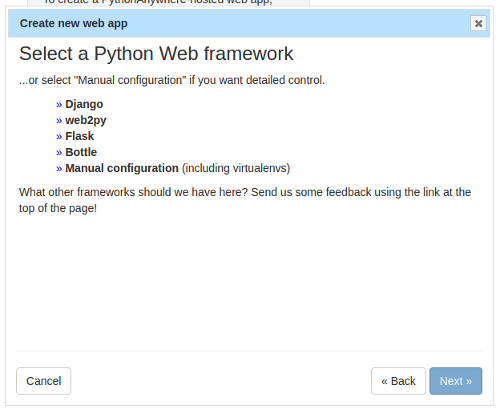

This page is where we select the web framework we want to use. This tutorial is for Flask, so click that one to go on to the next page.

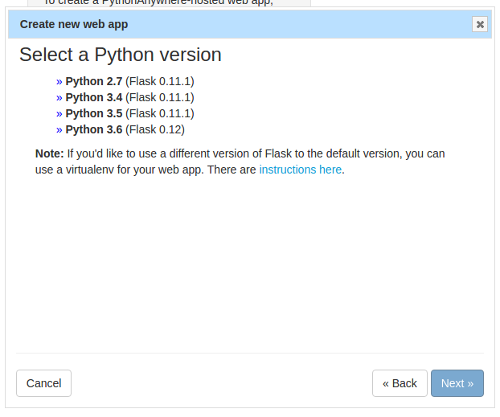

PythonAnywhere has various versions of Python installed, and each version has its associated version of Flask. You can use different Flask versions to the ones we supply by default, but it’s a little more tricky (you need to use a thing called a virtualenv), so for this tutorial we’ll create a site using Python 3.6, with the default Flask version. Click the option, and you’ll be taken to the next page:

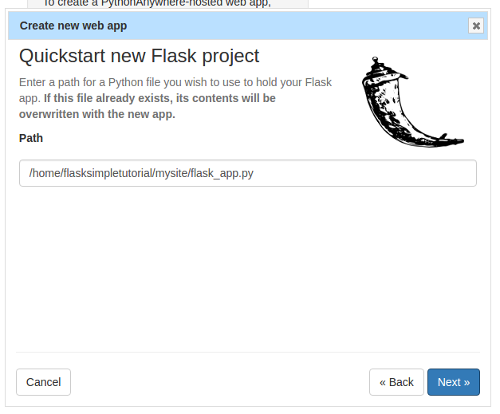

This page is asking you where you want to put your code. Code on PythonAnywhere is stored in your home directory, /home/yourusername, and in its subdirectories. Now, Flask is a particularly lighweight framework, and you can write a simple Flask app in a single file. PythonAnywhere is asking you where it should create a directory and put a single file with a really really simple website. The default should be fine; it will create a subdirectory of your home directory called mysite and then will put the Flask code into a file called flask_app.py inside that directory.

(It will overwrite any other file with the same name, so if you’re not using a new PythonAnywhere account, make sure that the file that it’s got in the “Path” input box isn’t one of your existing files.)

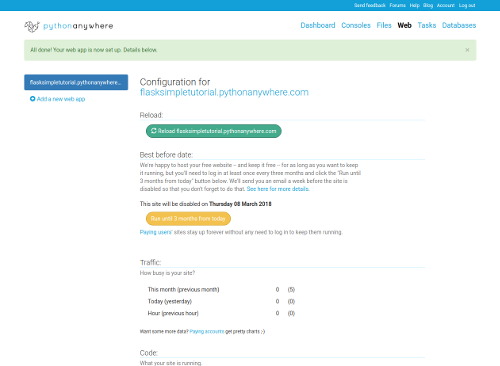

Once you’re sure you’re OK with the filename, click “Next”. There will be a brief pause while PythonAnywhere sets up the website, and then you’ll be taken to the configuration page for the site:

You can see that the host name for the site is on the left-hand side, along with the “Add a new web app” button. If you had multiple websites in your PythonAnywhere account, they would appear there too. But the one that’s currently selected is the one you just created, and if you scroll down a bit you can see all of its settings. We’ll ignore most of these for the moment, but one that is worth noting is the “Best before date” section.

If you have a paid account, you won’t see that – it only applies to free accounts. But if you have a free account, you’ll see something saying that your site will be disabled on a date in three months’ time. Don’t worry! You can keep a free site up and running on PythonAnywhere for as long as you want, without having to pay us a penny. But we do ask you to log in every now and then and click the “Run until 3 months from today” button, just so that we know you’re still interested in keeping it running.

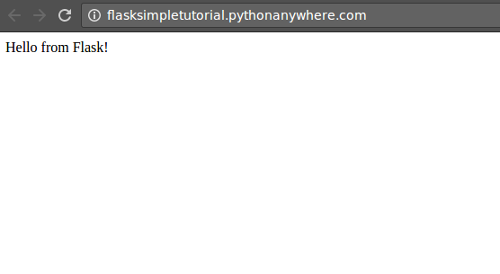

Before we do any coding, let’s check out the site that PythonAnywhere has generated for us by default. Right-click the host name, just after the words “Configuration for”, and select the “Open in new tab” option; this will (of course) open your site in a new tab, which is useful when you’re developing – you can keep the site open in one tab and the code and other stuff in another, so it’s easier to check out the effects of the changes you make.

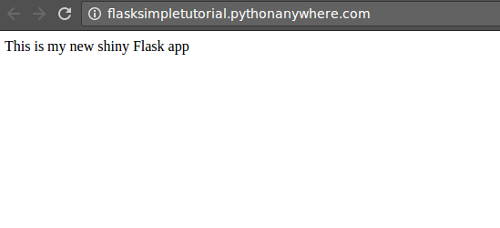

Here’s what it should look like.

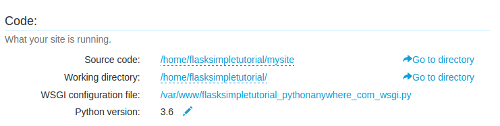

OK, it’s pretty simple, but it’s a start. Let’s take a look at the code! Go back to the tab showing the website configuration (keeping the one showing your site open), and click on the “Go to directory” link next to the “Source code” bit in the “Code” section:

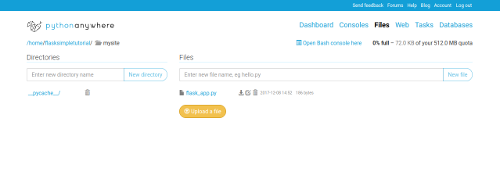

You’ll be taken to a different page, showing the contents of the subdirectory of your home directory where your website’s code lives:

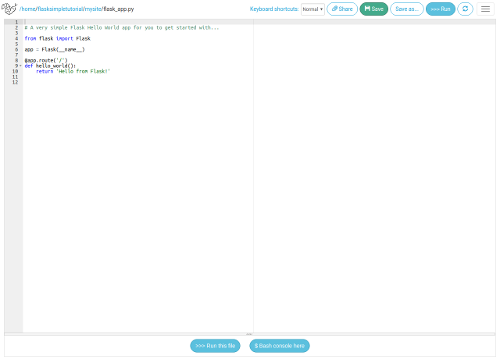

Click on the flask_app.py file, and you’ll see the (really really simple) code that defines your Flask app. It looks like this:

It’s worth working through this line-by-line:

from flask import Flask

As you’d expect, this loads the Flask framework so that you can use it.

app = Flask(__name__)

This creates a Flask application to run your code.

@app.route('/')

This decorator specifies that the following function defines what happens when someone goes to the location “/” on your site – eg. if they go to http://yourusername.pythonanywhere.com/. If you wanted to define what happens when they go to http://yourusername.pythonanywhere.com/foo then you’d use @app.route('/foo') instead.

def hello_world():

return 'Hello from Flask!'

This simple function just says that when someone goes to the location, they get back the (unformatted) text “Hello from Flask”.

Try changing it – for example, to “This is my new shiny Flask app”. Once you’ve made the change, click the “Save” button at the top to save the file to PythonAnywhere:

…then the reload button (to the far right, looking like two curved arrows making a circle), which stops your website and then starts it again with the fresh code.

A “spinner” will appear next to the button to tell you that PythonAnywhere is working. Once it has disappeared, go to the tab showing the website again, hit the page refresh button, and you’ll see that it has changed as you’d expect.

Keeping our code under control¶

OK, so we’ve seen the code, and we’ve changed it. Now, professional developers don’t change code without it being under some kind of source code control, so let’s get that set up before we change anything else.

(Coding without source-code control is basically trying to program with one hand tied behind your back. It’s possible, but you’re making stuff unnecessarily hard for yourself. With a source-code control system like git, you can “commit” your code at any point to make a place that you can easily get back to. So, before you embark on major changes, you can make sure that if you mess up, you can get back to where you were before you started: you’ll be able to roll back to the last working version. You can also do stuff like maintaining multiple parallel versions of your code – say, in-development and live – and, later on, you can easily collaborate with others. git is actually quite simple to use for the basic stuff, though it can get daunting, if not terrifying, once you get into the more advanced features. This tutorial will give the simple git commands you need to use for the basic checkpoint-rollback stuff, which is probably the most important bit.)

Back in the tab where you were editing the source code file, go back to the page showing the directory listing (by clicking the browser’s “Back” button, or clicking the second-last item, mysite, in the “breadcrumb” listing separated by “/” characters just above the editor). In the directory listing page, click the “Open bash console here” link near the top right.

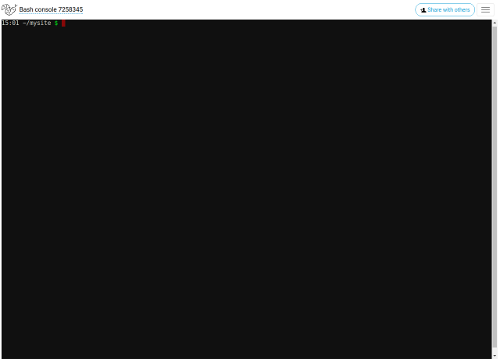

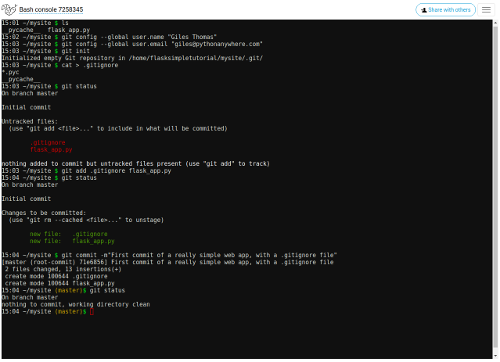

This will start an in-browser command line where you can enter bash commands – like git ones.

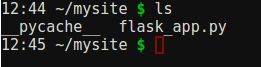

Type in the ls command to list the contents of the directory:

Right, let’s get that under source code control. Firstly, run the following two commands to configure git (replacing the stuff in the quotes appropriately):

git config --global user.name "Your Name"

git config --global user.email "you@example.com"

You won’t need to run that again on PythonAnywhere. The next step is to create a source-code control “repository” in this directory, which is another simple command:

git init

It should print out something like “Initialized empty Git repository in /home/yourusername/mysite/.git/”

Now, git is going to track all changes to files in this directory, but there’s some stuff we want it to ignore – temporary files created by Python and that kind of thing. You do this by creating a file called “.gitignore”. Let’s create one with some appropriate stuff for a Flask project in it; first, type this command:

cat > .gitignore

Anything you type into the console from now on will be added to the .gitignore file, so enter the following items, each on its own line:

*.pyc

__pycache__

Once you’ve entered the last one, and hit return, then type Control-D. This will go back to the bash “$” prompt.

Now we can ask git which files it can see. Type

git status

You’ll see something like this:

On branch master

Initial commit

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

.gitignore

flask_app.py

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

So, it’s saying that it doesn’t see any changes to files that it is tracking – which makes sense, because it hasn’t been told to track any files yet. But it can see two files that it isn’t tracking yet – our source file, and the .gitignore file we just created. We want it to track those files, so we type:

git add .gitignore flask_app.py

…to add them both. Run git status again to see what it thinks of that, and you’ll see something like this:

On branch master

Initial commit

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: .gitignore

new file: flask_app.py

So, now it knows about the files. We want to make a commit now – that is, we want to store the current state of the files in the repository so that we can get back to this state easily in the future. Run this command to make a commit with an appropriate comment (the bit in the quotes):

git commit -m"First commit of a really simple web app, with a .gitignore file"

It will print out something like this:

[master (root-commit) 962d9c7] First commit of a really simple web app, with a .gitignore file

2 files changed, 13 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 .gitignore

create mode 100644 flask_app.py

Now we can see what the status is after that by running git status again:

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

This means that as far as git is concerned, everything is in order.

Let’s make some changes so that we can show how to roll them back; go back to the code editing window, by clicking “Back” to get to the directory listing, then clicking on the source file again. Let’s add a new “view” – that is, a new URL that your web app will respond to. Right now, it will only handle requests to http://yourusername.pythonanywhere.com/ – it will respond with a “not found” error if, for example, you go to http://yourusername.pythonanywhere.com/wibble. (Check that in the tab where you’re viewing your website.)

So let’s add some code to handle the “/wibble” version. Just put this at the bottom of the source code file:

@app.route('/wibble')

def wibble():

return 'This is my pointless new page'

Click the “Save” button again, then the reload button, and check out your site on the tab you kept open earlier. Now, both http://yourusername.pythonanywhere.com/ and http://yourusername.pythonanywhere.com/wibble will work, and will return different text.

So that was our first change, but it was pretty pointless. Let’s use git to undo it. Click on the PythonAnywhere logo at the top left of the editor page, and you’ll be taken to the main PythonAnywhere dashboard. You’ll see that under “Recent Consoles” there’s a thing called something like “Bash console 5676757”.

When we opened the bash window earlier, it created a persistent console that will carry on running on PythonAnywhere, even when you’re not viewing it. (It may be reset due to server maintenance on our side, but in general it will keep running for a long time.) So if you click on it, it will take you back to where you were before:

Let’s see what git thinks is going on, by running git status again. You’ll get something like this:

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: flask_app.py

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

So it can see that we changed the flask_app.py file. That’s the change we want to undo. Usefully, it even tells us what to do to roll back a particular file. Run this:

git checkout -- flask_app.py

Run git status again, and you’ll see that it no longer sees that file as changed:

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

Let’s confirm that our change really was un-done. Click the PythonAnywhere logo again, then click on the flask_app.py file in the “Recent Files” list next to the “Recent Consoles” one. You’ll be taken to the editor again, and you’ll see that the pointless change has been backed out for us.

Hopefully that was at least instructive in showing how you can easily back out changes if you make a mess of your program while developing :-)

Right, now let’s start working on our app.

A first cut with dummy data¶

A web app in Flask, like most frameworks, consists of two kinds of file: source code, which is written in Python, and templates, which are written in an extended version of HTML. Basically, the source code says what the web app should do, and the templates say how it should be displayed.

Our website is just going to be a bunch of comments, one after another, with a text box at the bottom so that people can add new ones. So we’ll start off by writing a template that displays some dummy data, and a view in the Python code that renders (that is, displays) the template.

The template first. Click on mysite in the breadcrumb trail (remember, that’s the stuff separated by slashes at the top of the editor page), to get to your web app’s source code directory listing page. Templates go in a subdirectory of your source code directory, inventively called templates. So we can create that by typing “templates” into the “Enter new directory name” input near the top of the page, then clicking the “New directory” button next to it. That will take us to the directory listing for the new directory, which of course is empty. We’ll create our template file in there; type “main_page.html” into the “Enter new file name” input, and click the “New file” button next to it. This will take you to the editor, which will be empty.

Type the following HTML into the editor:

<html>

<head>

<title>My scratchboard page</title>

</head>

<body>

<div>

This is the first dummy comment.

</div>

<div>

This is the the second dummy comment. It's no more interesting

than the first.

</div>

<div>

This is the third dummy comment. It's actually quite exciting!

</div>

<div>

<form action="." method="POST">

<textarea name="contents" placeholder="Enter a comment"></textarea>

<input type="submit" value="Post comment">

</form>

</div>

</body>

</html>

Save it, and go back to the source code directory mysite using the breadcrumbs, and edit your source code file flask_app.py. We need to change it so that it renders that template. To do that, replace the existing view, which looks like this:

@app.route('/')

def hello_world():

return 'This is my new shiny Flask app'

…with one that looks like this:

@app.route("/")

def index():

return render_template("main_page.html")

You also need to change the line at the top that says

from flask import Flask

to import the render_template function too, like this:

from flask import Flask, render_template

Also, just to help in case you’ve made a typo in the code somewhere, add this line just after the line that says app = Flask(__name__)

app.config["DEBUG"] = True

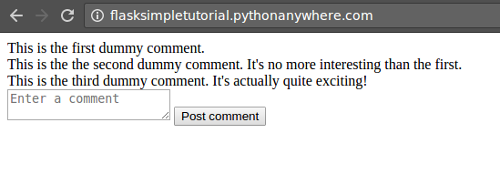

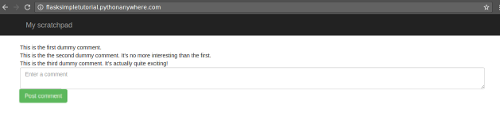

Now, save the file, reload the website, and refresh it in your other tab. It’ll look like this:

That’s pretty ugly, but it has our stuff from the template – it all worked :-)

Let’s take another checkpoint using git. This time, to save us from having to click around all the time, we’ll open up our bash console in a new browser tab. Go back to your source code editor tab, right-click the PythonAnywhere logo, and select the option to open the link in a new tab. In the new tab, click on the “Bash console XXXX” link (where XXXX is some number) under “Recent consoles”. You should now have three tabs open – the one where you’re editing your source code, the one with the bash console, and the one viewing your site.

In the bash console, type git status. It will say something like this:

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: flask_app.py

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

templates/

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

This means that it can see that we’ve changed flask_app.py, and also that we’ve added a directory called templates. It doesn’t say anything about what’s inside the templates directory.

We want to add both of these in one commit; taken together, the addition of a template and the code to render it make a single consistent change to our app, so it makes sense to bundle the two together. So, add the new directory

git add templates/

…and add the file

git add flask_app.py

Run git status to see what the situation now is:

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: flask_app.py

new file: templates/main_page.html

Now it’s telling us about the contents of the templates directory. (If we’d put more files into it, then the git add templates/ would have added all of them.)

So now we commit those changes to the repository in one, by running this command:

git commit -m"A first cut at the template"

It will print out something like this:

[master 4e8b505] A first cut at the template

2 files changed, 34 insertions(+), 4 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 templates/main_page.html

Now, it’s useful to know what’s happened in a repository in the past; so far we’ve done two commits. What do they look like? Run the command git log – it will print out the revision history, something like this:

commit 4e8b50560bb4ec32a273e3ad68faf1a8cb87fafa

Author: A PythonAnywhere dev <support@pythonanywhere.com>

Date: Fri Oct 30 17:39:34 2015 +0000

A first cut at the template

commit 962d9c7115a7169bcd6204b6c08911447cfd2e13

Author: A PythonAnywhere dev <support@pythonanywhere.com>

Date: Fri Oct 30 16:24:54 2015 +0000

First commit of a really simple web app, with a .gitignore file

You can see that there are two commits shown, with the most recent one at the top. Those complicated hexadecimal numbers just after the word “commit” are unique identifiers for the specific checkpoints you’ve made to your code. More advanced usage of git often involves using those identifiers to undo specific changes, or to pass sets of changes to other developers. But we won’t go into that here…

A less ugly site¶

So our change is committed. Let’s make the site look a bit prettier. Go back to your source code tab. Now we want to edit the template. We could do that here, but let’s open yet another tab so that we can switch between editing the different files easily. Right-click on the source code directory in the breadcrumb trail, and open it in a new tab. In the new tab, go to the templates subdirectory, then click on your main_page.html template file.

Now you have four tabs:

- The source code,

flask_app.py - The template,

main_page.html - The bash console for git

- The web site itself.

To make the site prettier, we’ll use the popular Bootstrap framework. Inside the <head> section of your HTML, before the title, add this:

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.3.5/css/bootstrap.min.css" integrity="sha512-dTfge/zgoMYpP7QbHy4gWMEGsbsdZeCXz7irItjcC3sPUFtf0kuFbDz/ixG7ArTxmDjLXDmezHubeNikyKGVyQ==" crossorigin="anonymous">

Save the file, then go to the tab that’s showing your site, and hit the page refresh button there. You’ll see that the font has become a bit nicer, but it’s still not super-pretty.

(Eagle-eyed readers will have spotted that this time we didn’t have to click the “Reload” button in the editor. For arcane technical reasons, you have to reload the web site every time you change Python code, but not when you change templates.)

Let’s improve things a bit more. In the template editor tab, add this at the start of the “Body” section:

<nav class="navbar navbar-inverse">

<div class="container">

<div class="navbar-header">

<button type="button" class="navbar-toggle collapsed" data-toggle="collapse" data-target="#navbar" aria-expanded="false" aria-controls="navbar">

<span class="sr-only">Toggle navigation</span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

</button>

<a class="navbar-brand" href="#">My scratchpad</a>

</div>

</div>

</nav>

<div class="container">

…then, at the end of the body, just before the </body> tag, add this:

</div><!-- /.container -->

Next, for each of the

<div>

lines containing our dummy comments, add class="row" before the close >, like this:

<div class="row">

Also add the same to the <div> that contains the <form>.

For the <textarea> tag, add class="form-control".

And finally, add a class to the button so that it looks like this:

<input type="submit" class="btn btn-success" value="Post comment">

Go to the tab showing your page, and refresh – it should look like this:

If it looks weird and ugly (or, at least, weirder and more ugly than that screenshot), check your HTML template and see if there are any obvious errors. It’s really worth spending some time trying to fix the errors yourself, as that’s the best way to learn how things work, but if you really find yourself struggling, here’s a complete copy of what should be in the template file so that you can copy and paste it into the editor:

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.3.5/css/bootstrap.min.css" integrity="sha512-dTfge/zgoMYpP7QbHy4gWMEGsbsdZeCXz7irItjcC3sPUFtf0kuFbDz/ixG7ArTxmDjLXDmezHubeNikyKGVyQ==" crossorigin="anonymous">

<title>My scratchboard page</title>

</head>

<body>

<nav class="navbar navbar-inverse">

<div class="container">

<div class="navbar-header">

<button type="button" class="navbar-toggle collapsed" data-toggle="collapse" data-target="#navbar" aria-expanded="false" aria-controls="navbar">

<span class="sr-only">Toggle navigation</span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

</button>

<a class="navbar-brand" href="#">My scratchpad</a>

</div>

</div>

</nav>

<div class="container">

<div class="row">

This is the first dummy comment.

</div>

<div class="row">

This is the the second dummy comment. It's no more interesting

than the first.

</div>

<div class="row">

This is the third dummy comment. It's actually quite exciting!

</div>

<div class="row">

<form action="." method="POST">

<textarea class="form-control" name="contents" placeholder="Enter a comment"></textarea>

<input type="submit" class="btn btn-success" value="Post comment">

</form>

</div>

</div>

</body>

</html>

OK, so we have a reasonably pretty page. Let’s get that committed into our git repository! Go to your Bash console tab, and run git status:

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: templates/main_page.html

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

It can see that we’ve just got changes to our template, so we add that file to the list of things to commit…

git add templates/main_page.html

…then we commit it.

git commit -m"Made the site prettier."

Run git status again to see that everything’s properly committed, and git log to see that the new commit has been added to the start of the list.

Sending and receiving data¶

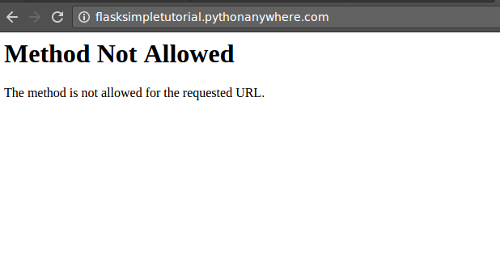

Let’s go back to the tab showing our site. Right now, if we type something into the text area for entering new comments, and click on the “Post comment” page, we’ll get a weird error – which makes perfect sense, as we haven’t written any code to store anything. Try it! You’ll get an error like this:

What this error means is that we tried to send data to the page, but it’s not configured to receive data, only to send it. When a browser accesses a page, it sends a message which contains an item saying what “method” it wants to use to access it. By convention, this is “GET” to view data, or “POST” to send data – that’s why the <form> tag in our template says method="POST". (Like everything in programming, it’s actually a bit more complicated than that, but that’s a good start :-)

Right now, our view only handles “GET” methods, because that’s what Flask views do by default. Let’s fix that; it’s really simple. Go to the tab showing your Python code, and replace

@app.route("/")

…with this:

@app.route("/", methods=["GET", "POST"])

Save the file, hit the reload button in the editor, then go to the tab showing your page; click back to get away from the error page if it’s still showing, then try to post a comment again.

Now you won’t get an error, but it will just take you back to the page you were viewing before, and completely forget your comment. Definitely a step forward, but not a very big one.

Let’s start storing the comments that people send us. We’ll do it an easy way first, without using a database, then we’ll add the database in later.

The easy way to store comments is just to do it in a variable inside the Python code. This is not great for the long run, because every time we reload the website, it will stop the program serving the site and then start it again, so all of the comments will be lost. Also, if you’re on a paid plan, you might have multiple processes running your code to handle your site (free plans have only one process for the whole site because they’re free, paid plans can have lots so that they can handle more simultaneous viewers) and each process will have different sets of comments. So we can’t use the variable-based version for the long run, but as a step forward it’s definitely worthwhile :-)

First, let’s define the variable. In the source code tab, add this in between the code that switches debug mode on, and the @app.route decorator:

comments = []

Next, change the contents of the index function so that it looks like this:

@app.route("/", methods=["GET", "POST"])

def index():

if request.method == "GET":

return render_template("main_page.html", comments=comments)

comments.append(request.form["contents"])

return redirect(url_for('index'))

Line-by-line, this means:

@app.route("/", methods=["GET", "POST"])

Specifies that the following function defines the view for the “/” URL, and that it accepts both “GET” and “POST” requests.

def index():

The name of the view function, of course

if request.method == "GET":

return render_template("main_page.html", comments=comments)

If the request we’re currently processing is a “GET” one, the viewer just wants to see the page, so we render the template. We’ve added an extra parameter to the call to render_template – the comments=comments bit. This means that the list of comments that we’ve defined as a variable further up will be available inside our template; we’ll update that to use the list in a moment.

If the request isn’t a “GET” (and so, we know it’s a “POST” – someone’s clicked the “Post comment” button) then the next bit is executed:

comments.append(request.form["contents"])

This extracts the stuff that was typed into the textarea in the page from the browser’s request; we know it’s in a thing called contents because that was the name we gave the textarea in the template:

<textarea class="form-control" name="contents" placeholder="Enter a comment"></textarea>

Once we’ve extracted the comment contents from the request, we add it to the list. Finally, once that’s been stored, we send a message back to the browser saying “Please request this page again, this time using a ‘GET’ method”, so that the user can see the results of their post:

return redirect(url_for('index'))

We just need to make one more change in our code: we’ve used a couple of new Flask functions and so we need to import them. Change

from flask import Flask, render_template

to this:

from flask import Flask, redirect, render_template, request, url_for

Save the file, then hit the reload button in the editor. Go to the tab showing your site, and have a play… unfortunately it still won’t do anything, even when you post a comment! This is because although we’ve added code to accept incoming comments, we’re not doing anything in the template to display them. So let’s fix that.

Go to the tab where you’re editing your template, and get rid of the three dummy comments:

<div class="row">

This is the first dummy comment.

</div>

<div class="row">

This is the the second dummy comment. It's no more interesting

than the first.

</div>

<div class="row">

This is the third dummy comment. It's actually quite exciting!

</div>

In their place, we’ll put a loop in the Flask template language that will iterate over all of the comments that we passed in to it in the render_template code in our Python code, and put in a <div> for each of them:

{% for comment in comments %}

<div class="row">

{{ comment }}

</div>

{% endfor %}

This should be pretty clear. Commands in the Flask template language, like for and endfor go inside {%..%}, and then you can also use {{..}} and a variable to insert the value of the variable at the current point.

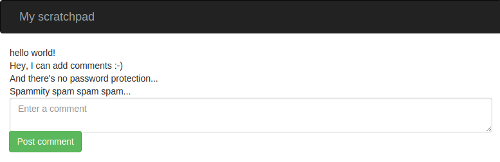

Now, save the file, and go to the tab showing your site. Hit the page refresh button – you’ll see that the dummy comments have gone, and if you posted some comments while you were trying it out before you updated the template, you’ll see those have been added instead! Try adding a few new comments; they’ll appear as soon as you post them.

If things don’t work, try to debug it. Check for typos in your code, and see if there are any errors displayed. If the worst comes to the worst and you really can’t work out what you mis-typed, here’s the code that you should have:

Python:

from flask import Flask, redirect, render_template, request, url_for

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config["DEBUG"] = True

comments = []

@app.route("/", methods=["GET", "POST"])

def index():

if request.method == "GET":

return render_template("main_page.html", comments=comments)

comments.append(request.form["contents"])

return redirect(url_for('index'))

Template:

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.3.5/css/bootstrap.min.css" integrity="sha512-dTfge/zgoMYpP7QbHy4gWMEGsbsdZeCXz7irItjcC3sPUFtf0kuFbDz/ixG7ArTxmDjLXDmezHubeNikyKGVyQ==" crossorigin="anonymous">

<title>My scratchboard page</title>

</head>

<body>

<nav class="navbar navbar-inverse">

<div class="container">

<div class="navbar-header">

<button type="button" class="navbar-toggle collapsed" data-toggle="collapse" data-target="#navbar" aria-expanded="false" aria-controls="navbar">

<span class="sr-only">Toggle navigation</span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

</button>

<a class="navbar-brand" href="#">My scratchpad</a>

</div>

</div>

</nav>

<div class="container">

{% for comment in comments %}

<div class="row">

{{ comment }}

</div>

{% endfor %}

<div class="row">

<form action="." method="POST">

<textarea class="form-control" name="contents" placeholder="Enter a comment"></textarea>

<input type="submit" class="btn btn-success" value="Post comment">

</form>

</div>

</div>

</body>

</html>

So, if everything’s working OK, it’s probably time to commit the changes. Over to the Bash console tab, and run git status yet again:

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: flask_app.py

modified: templates/main_page.html

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

This time, just for a change, let’s add our files to the list of files to commit and commit them in one go. This doesn’t work if you’ve created a new file, but as we’ve only modified existing ones, it’s an option. We just add an a before the m in the git commit command to say “add files”:

git commit -am"Replaced dummy comments with some in-memory storage"

Once again, run git status to confirm that everything’s now properly synchronized up, and git log to see your new commit in the history for the repository.

Password protection¶

So, we have a page where random people on the Internet can add comments. We all know what the Internet is like, and this is going to fill up with ads for fake Rolexes and dodgy pharmaceuticals pretty rapidly if we leave it open to the world. So let’s add some password protection. PythonAnywhere provides this for us.

To activate it, go to any of your tabs, right-click the PythonAnywhere to open the dashboard in a new browser tab, then click on the “Web” link near the top right. Make sure your website is selected on the left-hand side, then scroll to the bottom of the page. Just above the big red “delete” button there’s a section titled “Password protection”. Enter a username and a password here, and switch the toggle above those fields to “Enabled”. Scroll up to the top of the page again, and click the big green “Reload” button.

Now head over to the tab where you’re viewing your website, and refresh the page. This time you should be prompted for a password. You only need to enter it this one time for this browser session, so it won’t get in our way later on – but it will keep the spammers at bay… Once this is all done, you can close the browser tab where you set the password.

Bring on the database¶

Now it’s time to add a database in to the mix! You’ve probably already noticed the problem that adding one will solve; when you reloaded your website as part of enabling the password protection, all of your comments disappeared. So right now we have a site that will lose all of its data every time you reload it – which means, of course, every time you change the code. Not ideal.

We could store the comments in a simple file – and that would work fine for a basic site like this, but would become increasingly hard to maintain as we added new stuff in the future. Databases were designed to keep structured data in an easy-to-maintain, easy-to manage fashion, and that’s why we’re going to use one.

There are many database programs used for web apps; some examples are:

- SQLite, a simple lightweight database that keeps everything in a specially-formatted file on your disk. Not super-high-performance, but popular because it’s so simple.

- MySQL, which runs as a separate server process to which programs running on other machines can connect, storing data on the disks of the machine where it’s running. Fairly simple, pretty powerful. Probably the most popular option.

- PostgreSQL (for historical reasons, normally just called Postgres), which runs as a server, like MySQL, and is better with larger datasets. Growing in popularity, but needs a bit more server power to run.

- MongoDB, which allows you to store your data in a less-structured way than SQL databases like the previous three. Also server-based. New, slightly oddball – the hipster option.

SQLite is pretty slow on PythonAnywhere, and doesn’t scale well for larger sites anyway. Postgres is a paid feature on PythonAnywhere because of its larger server power requirements, and we don’t have built-in support for MongoDB. So we’re going to use MySQL, which you can use from a free PythonAnywhere account.

One convenient thing about modern database programming, however, is that to a certain degree you don’t need to worry about which database you’re actually using. There are database interface libraries called Object-Relational Mappers (ORMs), which make it possible (most of the time) to use the same code regardless of the underlying database. We’re going to use one called SQLAlchemy, which works well with Flask.

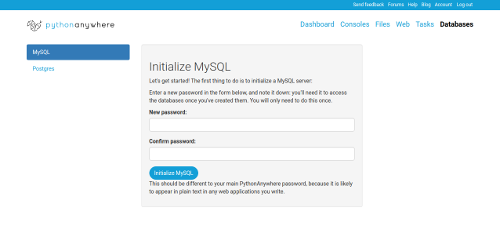

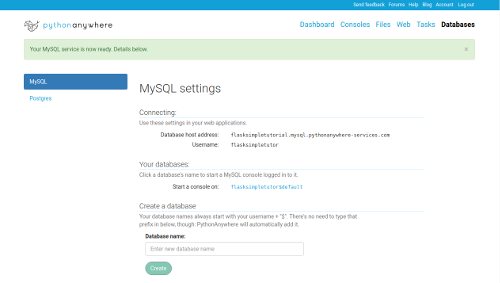

Right, enough background. Let’s create a MySQL database! In your tab where you’re editing the Python source code, right-click on the PythonAnywhere logo and open the page in a new tab. On the dashboard page that appears, click on the “Databases” link near the top right. You’ll wind up here:

The first thing you need to do to set up a MySQL database is specify the password you want to use when accessing it. Enter a new password here; make it something different to the one you use to log in to PythonAnywhere, because this database password will have to exist in your Python code (so that it can connect to your server), so it’s more secure to use a different one. Make a note of the password you’ve chosen, and once you’ve entered it twice in the appropriate fields, click the “Initialize MySQL” button. Wait for a few moments for your database to be set up, and you’ll come back to the “Databases” page, but now some extra options will have appeared:

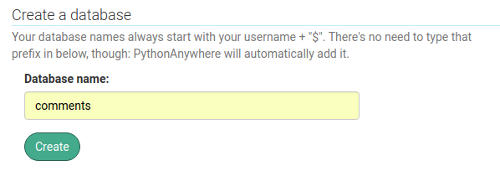

At the top, under “Connecting”, you’ll see the details you’ll need to connect to the MySQL server associated with your account. Next is a list of MySQL databases; one was created for you called yourusername$default, and there is also an option to create further databases. In general, it’s good practice to have a separate database for each website you’re working on to keep everything nicely separated. Go to the “Create database” section in the middle of the page, and create one, giving it the name “comments”:

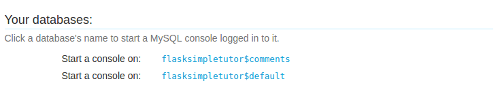

Once you’ve clicked the “Create” button, you’ll see it’s been added to the list that previously showed the yourusername$default one:

You can see that the database name is slightly different to the simple comments that you specified – it’s got your username and a dollar before it. (If your username is longer than 16 characters, it will be the username truncated to 16 characters.) This is simply to make sure that the name doesn’t clash with any other users’ databases that happen to be on the same server.

OK, so now we have a database. Let’s add some code to connect to it! Leave the databases page open, and switch back to the tab where you have your Python code. Just after the lines that say:

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config["DEBUG"] = True

…add the following code to configure the database connection:

SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI = "mysql+mysqlconnector://{username}:{password}@{hostname}/{databasename}".format(

username="the username from the 'Databases' tab",

password="the password you set on the 'Databases' tab",

hostname="the database host address from the 'Databases' tab",

databasename="the database name you chose, probably yourusername$comments",

)

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI"] = SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_POOL_RECYCLE"] = 299

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_TRACK_MODIFICATIONS"] = False

You need to change the values we set for username, hostname and databasename to the values from the “Databases” tab, and change the password to the one you set there earlier.

The first of these commands sets a variable to the specifically-formatted string SQLAlchemy needs to connect to your database. The second stashes that away in Flask’s application configuration settings.

The third sets an important database connection configuration parameter, which you don’t need to know the details of (though the following sidebar explains it in case you’re interested :-)

Sidebar: connection timeouts. Opening a connection from your website code to a MySQL server takes a small amount of time. If you opened one for every hit on your website, it would be slightly slower. If your site was really busy, the aggregate of all of the small amounts of time opening connections could add up to quite a slowdown. To avoid this, SQLAlchemy operates a “connection pool”. It keeps a set of connections to the database, and re-uses them. When you want a connection, it gives you one from the pool, creating a new one if the pool is empty, and when you’re done with it, the connection is returned to the pool for future reuse. However, in order to stop people from hogging database connections, MySQL servers close unused connections after a particular amount of time. On PythonAnywhere, this timeout is set to 300 seconds. If your site is busy and your connections are always busy, this doesn’t matter. But if it’s not, a connection in the pool might be closed by the server because it wasn’t being used. The SQLALCHEMY_POOL_RECYCLE variable is set to 299 to tell SQLAlchemy that it should throw away connections that haven’t been used for 299 seconds, so that it doesn’t give them to you and cause your code to crash because it’s trying to use a connection that has already been closed by the server.

The fourth line disables a SQLAlchemy feature that we’re not going to be using – explicitly saying that we don’t want to use it stops us from getting confusing warning messages later on.

So that’s the code that configures our database connection; now we need some code to actually connect to it! Put this just after the code you just added:

db = SQLAlchemy(app)

This simply creates a SQLAlchemy object using the connections we put into the Flask app’s config. We need to add an extra import statement to the start of our code to make this work, just after the other import that imports stuff from Flask:

from flask_sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemy

Right, we’ve added some code to connect to the database. Let’s sanity-check it and make sure we haven’t made any silly typos; hit the button to reload your website, and refresh the page in the other tab where you’re viewing it. If all is OK, you should get a site that behaves just like it did before. If there’s a problem, Flask should tell you what it is.

Once you’ve got everything working, go to the console where you’ve been doing git stuff, and use git commit to save a checkpoint.

Next, we need to add a model. A model is a Python class that specifies the stuff that you want to store in the database; SQLAlchemy handles all of the complexities of loading stuff from and storing stuff in MySQL; the price is that you have to specify in detail exactly what you want. Here’s the class definition for our model, which you should put in just above the line that says comments = []:

class Comment(db.Model):

__tablename__ = "comments"

id = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

content = db.Column(db.String(4096))

An SQL database can be seen as something similar to a spreadsheet; you have a number of tables, just like a spreadsheet has a number of sheets inside it. Each table can be thought of as a place to store a specific kind of thing; on the Python side, each one would be represented by a separate class. We have only one kind of thing to store, so we are going to have just one table, called “comments”. Each table is formed of rows and columns. Each row corresponds to an entry in the database – in our simple example, each comment would be a row. On the Python side, this basically means one row per object stored. The columns are the attributes of the class, and are pretty much fixed; for our database, we’re specifying two columns: an integer id, which we’ll use for housekeeping purposes later on, and a string content, which holds, of course, the content of the comment. If we wanted to add more stuff to comments in the future – say, the author’s name – we’d need to add extra columns for those things. (Changing the MySQL database structure to add more columns can be tricky; the process is called migrating the database.

The second part of our tutorial covers that.)

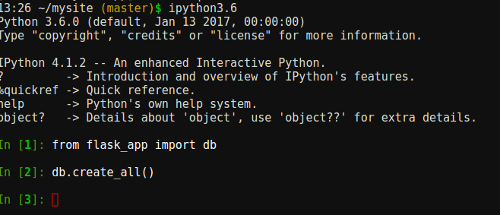

Now that we’ve defined our model, we need to get SQLAlchemy to create the database tables. This is a one-off operation – once we’ve created the database’s structure, it’s done. Save your Python file, then head over to the bash console we’ve been using so far for git stuff, and run ipython3.6 to start a Python interpreter (if you chose a different Python version for your website, just replace the 3.6 with the version that you used).

Once it’s running, you need to import the database manager from your code:

from flask_app import db

Now, we want to create the tables. This is really easy:

db.create_all()

Once you’ve done that, the table has been created in the database. Let’s confirm that. Go to the tab you kept open that’s showing the “Databases” PythonAnywhere page, and click on your database name (yourusername$comments). This will start a new console, running the MySQL command line. Once it has loaded (it will show a mysql> prompt), run the command:

show tables;

(Don’t forget the semicolon at the end!)

This should show you that you have a table called comments. To inspect it and make sure that it has the stuff you’d expect, run the command:

describe comments;

You’ll see that we have two columns, one called id, and one called content – just as you’d expect from the class definition in our Python code!

Let’s do another checkpoint. Go back to the tab where you previously did the git stuff, and more recently used the Python interpreter to create the tables. Exit the Python interpreter, using Control-D or exit(). Now let’s try out a new git command:

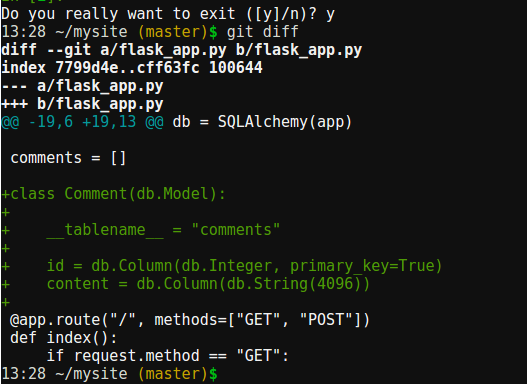

git diff

You’ll see that git prints out all of the changes to your code in green, with a bit of code around it in white for context:

That’s often useful when you’ve not done a commit for a while and need a reminder of what you’ve changed. For now, just do a git add and a git commit to save your changes.

So now we have code in our Flask app to connect to the database, a Python definition of what we want to store in the database, and tables created in the database on the MySQL server to store the data. Let’s add the code to actually use all of that!

Firstly, we can get rid of the line where we create the old in-memory storage for the comments, the one like this:

comments = []

Once that’s deleted, we can change the code that uses it in the index view. Firstly, let’s write code to load all of the comments from the database and pass them to the template rather than use the in-memory variable. Replace this line:

return render_template("main_page.html", comments=comments)

…with this:

return render_template("main_page.html", comments=Comment.query.all())

The query attribute is something that SQLAlchemy added to your Comment class allowing you to make queries to the database, and its all method, like you’d expect, just gets all comments.

Now, we need to change the template. Previously, our in-memory list of comments was just a list of strings. Now that we’ve changed it to query the database, the template is getting a list (or something that will act like a list) of Comment objects. We want to get their content attribute, and the change is pretty much like you’d expect. In the editor for the template, change the bit inside the for loop where we insert the comment:

{{ comment }}

…to this:

{{ comment.content }}

Now we’ve implented the code to display comments, but we still need to write code to add them. Back in the editor for the Python code, replace this:

comments.append(request.form["contents"])

…with this:

comment = Comment(content=request.form["contents"])

db.session.add(comment)

db.session.commit()

The first line creates the Python object that represents the comment, but doesn’t store it in the database. The second sends the command to the database to store it, but leaves a transaction open. Transactions allow you to batch up a bunch of changes into one, for efficiency and also so that if an error occurs you can easily abort and have none of them happen; basically it’s a way of batching things up into a set of small changes that, taken together, make one logically coherent larger change. As we’re only making one change – adding one comment – then we can commit immediately, which closes the transaction and stores everything. (You can probably see a similarity between this “prepare things and when you’ve got a bunch of things ready, commit to store it all” and the git add followed by git commit commands we’ve been using for git. That’s no coincidence! It’s a common pattern across lots of areas of programming.)

OK, so we have code to load comments from the database and code to store them in the database. We’re done! Save the file, and hit the button at the top of the editor to reload the website, and go over to the tab where you have it open. Refresh the page; it should be the normal page with no comments yet. Type one in, and click the “Post comment” button. It will appear.

Now, the acid test to prove that it’s being stored in the database and can survive a website reload: go to the editor window again, and click the button to reload your web app. Wait until it’s done, then go back to the website. Refresh the page…. and your comment will still be there!

Ta-dah!

Let’s make one final sanity check; we can inspect the database directly and see what’s in there. Go back to the MySQL command window that you opened earlier, and run this command:

select * from comments;

In lovely 1970s-style ASCII-art table graphics, you’ll get the contents of your database – one shiny new row (or more if you’ve entered multiple comments):

+----+-------------------------------------------+

| id | content |

+----+-------------------------------------------+

| 1 | This is my first comment for the database |

+----+-------------------------------------------+

1 row in set (0.00 sec)

Once again, if things don’t work, try to debug it. Check for typos in your code, and see if there are any errors displayed. If the worst comes to the worst and you really can’t work out what you mis-typed, here’s the code that you should have:

Python:

from flask import Flask, redirect, render_template, request, url_for

from flask_sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemy

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config["DEBUG"] = True

SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI = "mysql+mysqlconnector://{username}:{password}@{hostname}/{databasename}".format(

username="the username from the 'Databases' tab",

password="the password you set on the 'Databases' tab",

hostname="the database host address from the 'Databases' tab",

databasename="the database name you chose, probably yourusername$comments",

)

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI"] = SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_POOL_RECYCLE"] = 299

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_TRACK_MODIFICATIONS"] = False

db = SQLAlchemy(app)

class Comment(db.Model):

__tablename__ = "comments"

id = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

content = db.Column(db.String(4096))

@app.route("/", methods=["GET", "POST"])

def index():

if request.method == "GET":

return render_template("main_page.html", comments=Comment.query.all())

comment = Comment(content=request.form["contents"])

db.session.add(comment)

db.session.commit()

return redirect(url_for('index'))

HTML template:

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.3.5/css/bootstrap.min.css" integrity="sha512-dTfge/zgoMYpP7QbHy4gWMEGsbsdZeCXz7irItjcC3sPUFtf0kuFbDz/ixG7ArTxmDjLXDmezHubeNikyKGVyQ==" crossorigin="anonymous">

<title>My scratchboard page</title>

</head>

<body>

<nav class="navbar navbar-inverse">

<div class="container">

<div class="navbar-header">

<button type="button" class="navbar-toggle collapsed" data-toggle="collapse" data-target="#navbar" aria-expanded="false" aria-controls="navbar">

<span class="sr-only">Toggle navigation</span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

<span class="icon-bar"></span>

</button>

<a class="navbar-brand" href="#">My scratchpad</a>

</div>

</div>

</nav>

<div class="container">

{% for comment in comments %}

<div class="row">

{{ comment.content }}

</div>

{% endfor %}

<div class="row">

<form action="." method="POST">

<textarea name="contents" placeholder="Enter a comment" class="form-control"></textarea>

<input type="submit" class="btn btn-success" value="Post comment">

</form>

</div>

</div><!-- /.container -->

</body>

</html>

Conclusion¶

So now we have a website that will allow people to enter random comments, and will remember them even if the website is reloaded. Everything has been coded in Flask, and the data is stored in MySQL using SQLAlchemy. One last thing before we can call this done, though – go over to the console where you’ve been running git, and do one last git commit:

git commit -am"Yay, it's all finished :-D"

You’ve built a simple database-backed Flask website on PythonAnywhere.

I hope it all went smoothly for you, and if you had any problems, just post a comment below!

If you’re thinking of developing this app further, you can check out the second part of our Flask tutorial here.

Thanks for reading!